by Bruce Bethke

by Bruce BethkePerhaps we should be classified as a semi-aquatic species. Our large brains and nimble hands enable us to make the tools we need to adapt to almost any environment, from equatorial desert to polar sea and from the bottom of the ocean to the hard vacuum of space, but in our natural form we thrive best in the littoral zones, in temperate to tropical climates.

And as any mother can tell you, put a boy near the water, and pretty soon he's in the water. And then on it, using anything that can be made to float. Where there are forests, we use logs. Deprive us of trees, and we use bundles of reeds, or animals hides stretched over frames, or even greased skins, tied tightly and inflated to make primitive pontoons. Pretty soon we're busy figuring out how to hollow out and reshape our logs, to make them float even better.

Put two of us on the water, and immediately we're in competition, to see who can go farther, faster, or knock the other guy off his log. Pretty soon one bright lad figures out that if he uses a stick to push off the bottom, he can move faster and maneuver better. Another realizes that if he sharpens one end of the stick, he can spear fish and eat better. A third realizes that if he specializes, and uses a wide stick for paddling and a thin stick for spearing, he can catch even more fish and eat better still. And then one very bright lad realizes that if he uses a stick to hold up something that can catch the wind, he can move fastest of all.

Which is right about the point when one of the first three lads realizes that if he uses his stick to knock that smartass off his raft, he can take it for himself. Which is roughly where things stood, for unknown tens of thousands of years.

There are times I marvel at just how thoroughly and yet unconsciously our species and our cultures have been shaped by water, and by the free energy we get from the solar convection cycle of evaporation, condensation, wind and rain. Where the rivers flow downhill with sufficient urgency we plant sawmills and grain mills, which in time grow up to become towns and cities. Where the rivers flow year-round they become highways, and where the winds are steady and predictable, we develop trade routes. A careless science fiction or fantasy writer might site cities and fortresses where they best suit his or her dramatic purposes, but out here in the real world, our cultures grow up along the banks of great rivers, or on the coasts of seas, or among the island chains of archipelagos.

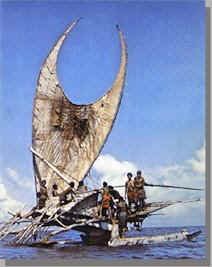

We build our hulls from whatever we can find, and craft our sails from a bewildering variety of materials and in a remarkable variety of shapes. We make boats not for the curiosity of it all; not to explore, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no Ngeremlenguian has gone before; but to find new and bigger fish to catch, new markets to sell to, and new trade goods to bring home and sell for a handsome profit. And if fortune should lead us to find new lands where there are other people who are not as well-armed nor as warlike as ourselves? Then that, too, can be very, very profitable.

We build our hulls from whatever we can find, and craft our sails from a bewildering variety of materials and in a remarkable variety of shapes. We make boats not for the curiosity of it all; not to explore, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no Ngeremlenguian has gone before; but to find new and bigger fish to catch, new markets to sell to, and new trade goods to bring home and sell for a handsome profit. And if fortune should lead us to find new lands where there are other people who are not as well-armed nor as warlike as ourselves? Then that, too, can be very, very profitable. Which is approximately the way things stood, until... 1945?